Kirkwood native preserved her father’s banking legacy

MONMOUTH, Ill — Growing up in Monmouth during the 1970s, one of the interesting landmarks I recall was a circular brick fountain in front of the National Bank of Monmouth’s Colonial Drive-In on East Broadway. It was particularly memorable because of a recurring nighttime prank by members of a Monmouth College sorority, who would drop a Salvo laundry tablet into the basin and by morning the fountain would be overflowing with suds.

Affixed to the masonry was a bronze plaque, announcing that it was the Myra Tubbs Ricketts Memorial Fountain. I always chuckled at that name, especially having no idea who Mrs. Ricketts was or why a fountain would be named for her. A few years later, however, when I became an employee of the National Bank, I would learn all about the Tubbs and Ricketts families, and about Myra’s prominent role in the bank’s history.

Born in Kirkwood in 1871, Myra was the daughter of Dr. Henry Tubbs — the patriarch of a family that made an enormous impact on the banking industry in western Illinois. To appreciate those contributions, a brief biography of the doctor is in order.

A bookish, frail child who was born on a farm in New York in 1822, Tubbs’ early education was often interrupted by farm work, until he was able to escape to an academy, where he learned and eventually taught, then spent time peddling books in New York City and driving horses for Erie Canal boats.

Tubbs’ passion was medicine, and not being able to afford medical school, he studied under a local physician, who turned an increasingly large amount of work over to him. Tubbs came to believe that many of the medical practices of the day such as bleeding were quackery, and he decided to pursue a career preaching and practicing conservative medicine.

Eventually, Tubbs saved enough to enter and graduate from a small medical college in Georgia, which embraced his scientific philosophy. He set up shop in Cleveland, Ohio, and soon gained so many patients that his health was nearly ruined due to overwork. He decided to abandon medicine and in 1859 traveled to Young America (now Kirkwood), Illinois, where his family had established a farm. Here, he regained his health and took over management of the farm during the Civil War.

Seeing a need for a local supplier of farm implements and hardware, Tubbs partnered in 1863 with John Sofield and established a Kirkwood hardware store that thrived until 1874, when Tubbs left to form a private bank. The following year, it became the First National Bank of Kirkwood, with Tubbs as president and Sofield as a director.

As his career flourished, Tubbs also devoted an enormous amount of time to civic work, serving as chairman of the Warren County board of supervisors, as a member of the 1870 Illinois Constitutional Convention, and as a delegate to both the 1872 and 1880 Republican National Conventions. From 1882 to 1886, he was a member of the Illinois Senate, serving as chairman of the Committee on Banks and Banking. He was also a charter member of the Warren County Library board, which he served until his death.

Because Tubbs didn’t marry until he was 46 years old, he took a special interest in the children and grandchildren of his older brother, James — many of whom were employed in the banks he founded. In 1884, when he was a senator and 62 years old, Tubbs purchased the Monmouth National Bank stock of its president, William Hanna, and became president of that bank. At the same time, he remained president of the Kirkwood and Alexis banks.

Tubbs had built a fine Second Empire-style mansion in Kirkwood in 1878. Every morning for 15 years, he took the 8 o’clock train to Monmouth, where he would walk to his office at the National Bank, and then walk back to the depot to catch the 6 o’clock train home.

Upon Tubbs’ death in 1899, the three bank presidencies became vacant. His sole surviving son, Shirley, became a director of all three banks and assistant cashier of the Kirkwood bank, while his nephew, Willard Tubbs, became president of the Kirkwood bank. Shirley organized the Bank of Cameron and in 1902 became president of the National Bank of Monmouth, but only five years later he died in India during a round-the-world tour.

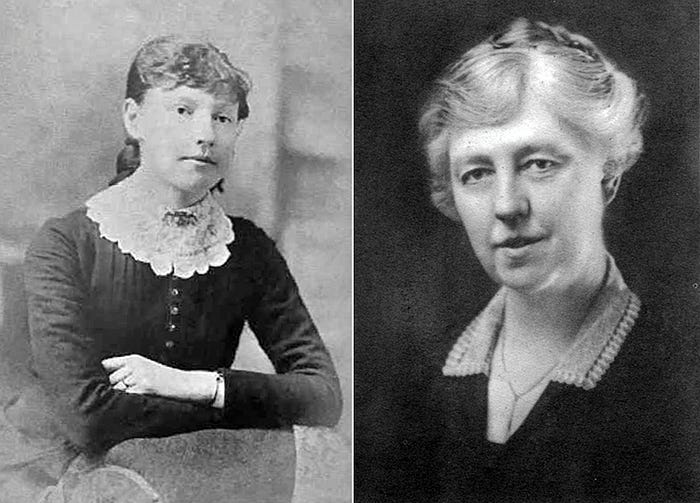

With no male heir of Henry Tubbs remaining, Kirkwood bank president Willard Tubbs also assumed the presidency of the Monmouth bank. Meanwhile, Henry’s daughter, Myra, was enjoying life in Chicago as a mother and the wife of Dr. Howard Taylor Ricketts, a gifted scientist whom she had met while a student at Northwestern University. However, she graciously agreed to become a director of the Monmouth and Kirkwood banks.

Myra’s husband had worked at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, and became a researcher in bacteriology at the University of Chicago. He began studying the bacteria that caused Rocky Mountain spotted fever and deduced it was related to typhus. His research took him to Mexico, where ironically he contracted typhus and died in 1910, leaving Myra a young widow raising a son, Henry, and a daughter, Elisabeth.

When her cousin Willard died in 1921, Myra Tubbs Ricketts became president of the Kirkwood bank, serving in that position for five years. As a director of the National Bank of Monmouth, she had been an influential member of the committee that erected its new building (now City Hall) in 1916.

During the farm foreclosures of the 1930s, Myra would go to auctions with her cousin, the family farm manager, to try to force bids up if the price was too low to cover the mortgages at the bank. When correspondent banks in Alexis and Roseville faltered, she was instrumental in merging them with the Monmouth bank. In 1932, her beloved Kirkwood bank, which had already absorbed three troubled banks, was at last forced to merge with the Monmouth bank. Determined that “no one will ever lose a dollar in a Tubbs bank,” she visited her safe deposit box in Chicago and removed her bonds, which she signed over to the Monmouth bank as security for poor loans. As a result, no one ever did lose a dollar.

Myra continued to help steer the National Bank as a director until her death in 1953 at age 81. Myra’s son, Dr. Henry Tubbs Ricketts, served as director of the National Bank for 40 years. A Harvard-trained professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, he was an authority on the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Myra’s daughter, Elisabeth — also a longtime director of the bank — married Dr. Walter Palmer, a pioneer in the field of gastroenterology.

Elisabeth Palmer’s three sons — Donald, Henry and Robert — also became successful physicians. Henry was also a fourth-generation director of the National Bank, serving 10 years on its board. Elisabeth’s daughter, Betsy Eldridge, who makes her home in Toronto, is dedicated to preserving the legacy of Dr. Tubbs and his mansion in Kirkwood, and has made regular visits there for years.

Jeff Rankin is an editor and historian for Monmouth College. He has been researching, writing and speaking about western Illinois history for more than 40 years.